Esto sugiere que el hielo se retiró profundamente en el continente después del final de la última edad de hielo y re-avanzado antes de que comenzara la retirada moderna, concluye el estudio, publicado en AGU Advances. Presenta la primera restricción geológica para la ubicación y el movimiento de la capa de hielo desde la última edad de hielo.

"En los últimos miles de años antes de que comenzáramos a observar, el hielo en algunas partes de la Antártida retrocedió y volvió a avanzar en un área mucho más grande de lo que apreciamos anteriormente", dijo en un comunicado Ryan Venturelli, paleoglaciólogo de la Escuela de Minas de Colorado y autor principal del nuevo estudio. "El retroceso en curso del glaciar Thwaites es mucho más rápido de lo que hemos visto antes, pero en el registro geológico, vemos que el hielo puede recuperarse", destacó.

La línea de puesta a tierra es donde un glaciar o capa de hielo deja tierra firme y comienza a flotar en el agua como una plataforma de hielo. Hoy en día, la plataforma de hielo de Ross se extiende cientos de kilómetros sobre el océano desde la línea de puesta a tierra de la capa de hielo de la Antártida occidental. Debido a que el agua del océano se lava contra el borde de ataque del hielo, la línea de conexión a tierra puede ser una zona de rápido derretimiento.

"La preocupación por la pérdida de hielo en tierra se debe a que la pérdida de hielo en tierra es lo que contribuye al aumento del nivel del mar", dijo Venturelli. "A medida que las líneas de conexión a tierra se retiran tierra adentro, más vulnerable se vuelve la capa de hielo, ya que expone hielo cada vez más grueso al calentamiento del océano".

Durante el Último Máximo Glacial, hace unos 20.000 años, la capa de hielo de la Antártida Occidental era tan grande que estaba asentada en el fondo del océano, más allá del borde del continente. Las observaciones anteriores generalmente indican un retroceso constante desde entonces, acelerado en el siglo pasado por el cambio climático causado por el hombre.

La pregunta para Venturelli era hasta qué punto tierra adentro se había retirado la capa de hielo después de la última edad de hielo. Sin saber eso, es difícil predecir qué tan sensible es la capa de hielo de la Antártida y cómo responderá a un mayor cambio climático.

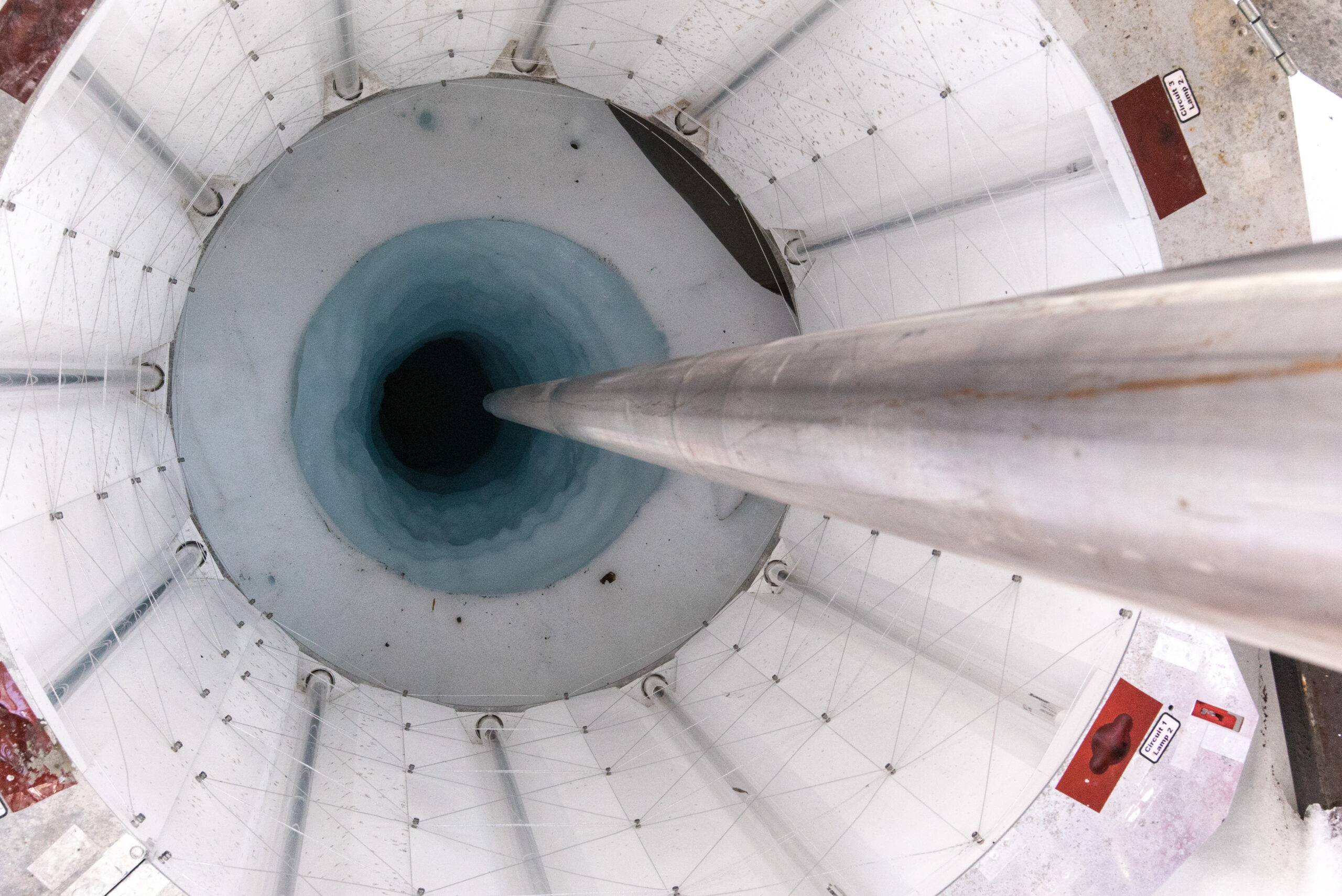

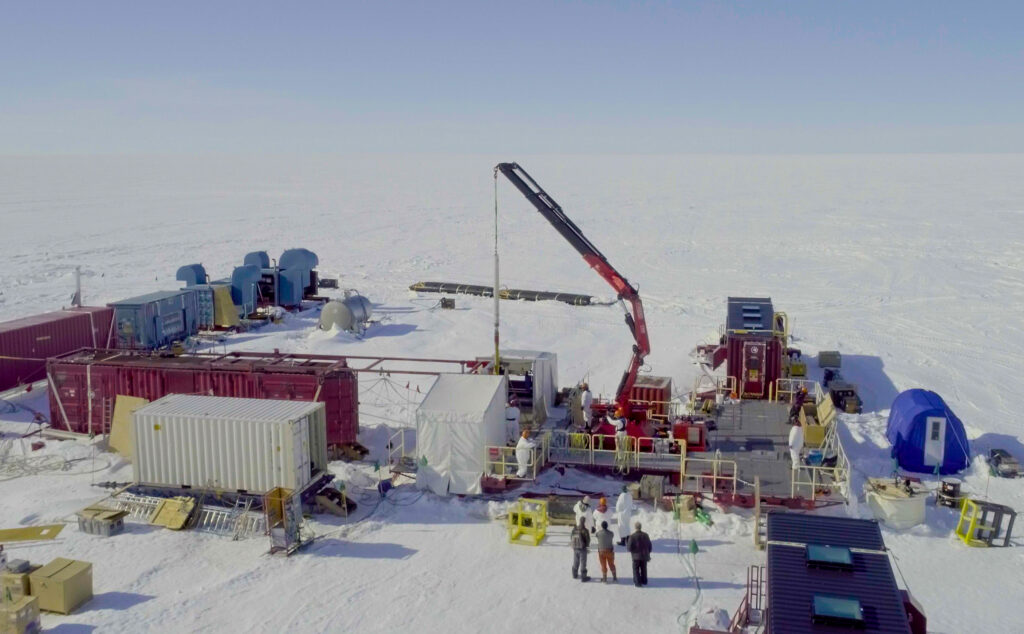

Un lago de aproximadamente el doble del tamaño de Manhattan enterrado bajo un kilómetro de hielo y aislado de la atmósfera actual contenía pistas para la respuesta. Para alcanzarlo, Venturelli y su equipo se abrieron paso cuidadosamente con un "taladro" de agua caliente. Una vez que tuvieron acceso, sacaron muestras de agua del lago y sedimentos llenos de carbono del lecho del lago. Utilizando la datación por radiocarbono, encontraron que el carbono tenía unos 6.000 años.

Debido a que el radiocarbono (carbono-14) en estos sedimentos debe haber venido del agua de mar, el hallazgo sugiere que lo que ahora es un lago a 150 kilómetros del borde del hielo moderno era el fondo del océano. Cuando el hielo avanzó, tapó el lago, conservando el carbono como parte de los sedimentos del fondo del lago. Y según el radiocarbono en la muestra de agua, la línea de conexión a tierra podría haber estado 100 kilómetros incluso más hacia el interior en ese momento.

"Cuando nos dispusimos a tomar muestras de este lago, no estábamos seguros de lo que encontraríamos sobre la historia del hielo, pero el hecho de que la desglaciación persistiera tan tierra adentro no era una posibilidad tan descabellada", dijo Venturelli. "Esta área de la Antártida occidental es realmente plana. No hay nada que frene el retroceso de la línea de puesta a tierra. No hay topes topográficos reales".

La nueva evidencia de la capacidad del hielo antártico para reavanzar fue una buena noticia para Venturelli.

"A veces puede ser un fastidio estudiar la pérdida de hielo en la Antártida", dijo. "Aunque el re-avance identificado en el registro geológico ocurre durante miles de años, me gusta pensar en estudiar el proceso de reversibilidad como una pequeña pizca de esperanza".

La próxima gran pregunta para Venturelli y sus coautores es evaluar qué condiciones permitieron el nuevo avance del hielo. Una posibilidad es el rebote después de la liberación del peso masivo de la capa de hielo que levantó la tierra lo suficiente como para contener el océano y permitir que el hielo vuelva a crecer. Otra posibilidad es que ligeros cambios en el clima permitieron que la capa de hielo pasara de retroceder a avanzar. Podría haber sido una combinación de estas influencias.

Fuente: