En agosto de 2002, en plena crisis económica argentina -una de tantas-, The New York Times publicó un artículo que resonó como un eco incómodo: "Algunos en Argentina ven la secesión como la respuesta al peligro económico".

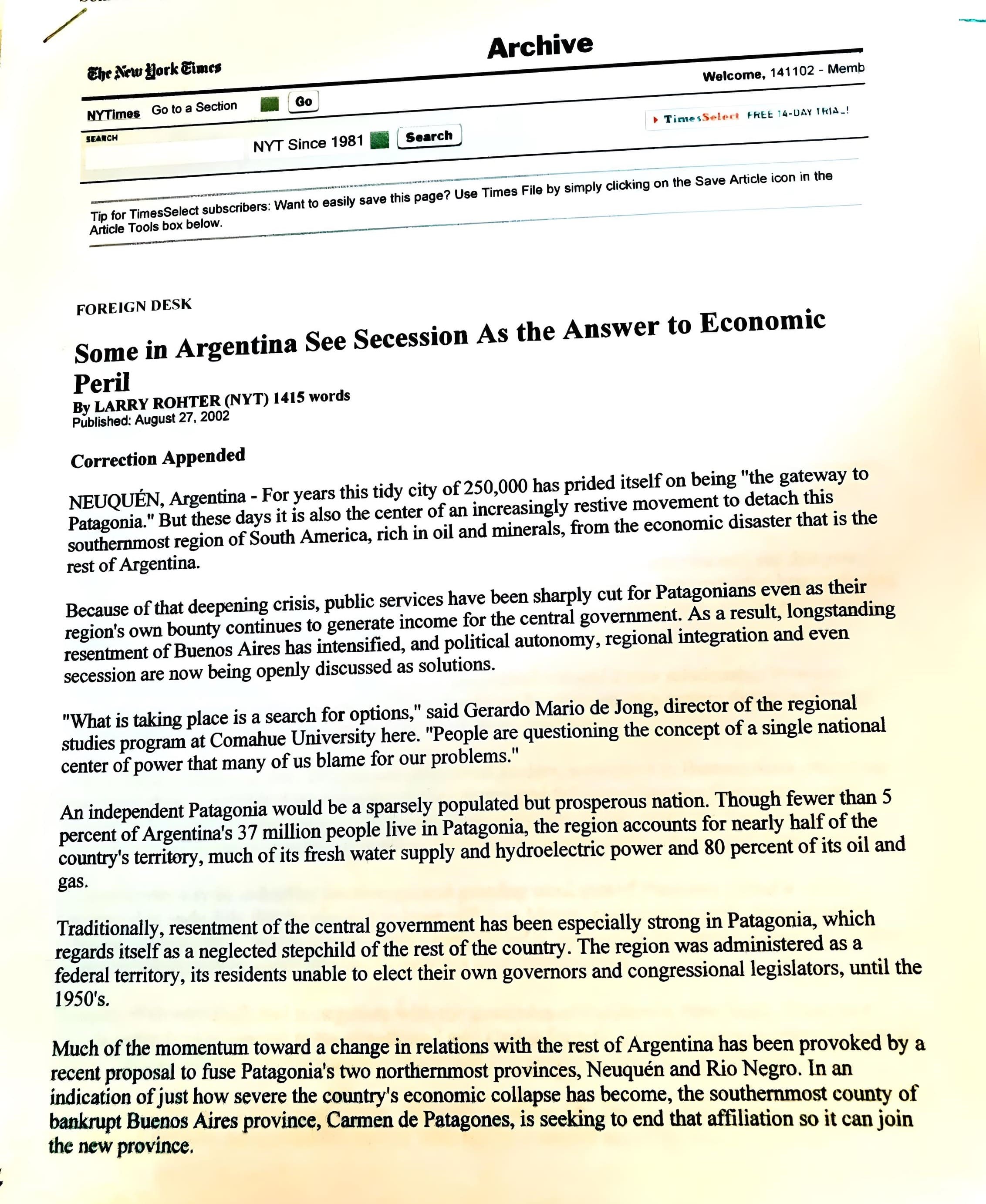

Copy de la publicación del 26 de agosto de 2002, realizada por The New York Time.

Firmado por Larry Rohter, el reportaje exploraba el malestar patagónico ante el centralismo porteño y la tentación de una independencia forjada en la riqueza petrolera, hidroeléctrica y mineral de la región.

Hoy, en un contexto radicalmente distinto, pero igualmente polarizado, aquel texto resurge en el debate público, ahora vinculado al controvertido acuerdo del presidente Javier Milei con Israel, que incluye facilidades para la radicación de ciudadanos y empresas israelíes en la Patagonia.

El artículo de Rohter retrataba una región exasperada: supuestamente el 53% de los encuestados en 2002 apoyaba la secesión, cifra que escalaba al 78% entre los jóvenes. El resentimiento hacia Buenos Aires, acusada de expoliar recursos sin retorno, se mezclaba con una identidad patagónica diferenciada, alimentada por la diversidad migratoria (españoles e italianos, pero además galeses, croatas y alemanes) y la lejanía geográfica. "Nos llevan petróleo, gas y madera, y solo nos devuelven problemas", declaraba entonces Elfo Kruteler, un profesor de francés citado en el reportaje.

Dos décadas después, los términos del conflicto mutan, pero no desaparecen.

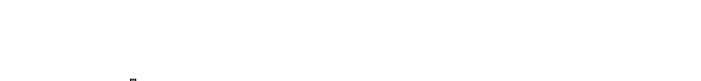

El reciente convenio entre el gobierno argentino de Javier Milei con un Israel conducido por Benjamin Netanyahu, firmado en medio de la condena global a los ataques israelíes en Gaza, ha encendido alarmas sobre una posible extranjerización de la Patagonia. Para algunos, el fantasma de 2002 revive: la región, otra vez, como botín geopolítico. "Siempre somos los olvidados", decía en el artículo Alicia Rosa, una patagónica de, entonces, 54 años. Hoy, esa frase podría leerse junto a los cuestionamientos al acuerdo con un Estado acusado de violaciones sistemáticas a los derechos humanos.

Reunión de Javier Milei con Benjamin Natanyahu, el pasado 10 de junio; donde el primer ministro israelí observa un mapa de argentina centrado en patagonia.

En 2002, el gobierno de Eduardo Duhalde desestimó las pretensiones independentistas como "pura idiotez", aunque reconocía la necesidad de reformular el federalismo. El gobernador neuquino de aquel momento, Jorge Sobisch (de ascendencia croata), negaba la secesión, pero exigía autonomía: "¿Por qué ser prisioneros de un sistema ineficiente?".

La privatización de YPF y la venta de tierras a Benetton y Ted Turner alimentaban la desconfianza hacia Buenos Aires. Hoy, el temor ya no es la venta de parques nacionales -rumor en 2002-, sino la instalación de bases militares y capitales extranjeros en un marco de crisis económica y ajuste.

El paralelo entre ambas épocas revela una constante: la Patagonia como territorio en disputa, entre la marginalidad histórica y su potencial estratégico. En 2002, Rohter citaba a un docente militar que advertía sobre planes castrenses ante una hipotética secesión. Hoy, son las cláusulas de cooperación en materia de educación y defensa con Israel las que generan suspicacias.

La pregunta que el Times formuló en 2002 resurge ahora, con nuevos actores: ¿puede el abandono histórico y la riqueza mal administrada convertir a la Patagonia en un polvorín? El reportaje de Rohter terminaba con una advertencia de Rubén Reveco, editor patagónico: "Cuando una familia está endeudada, vende lo prescindible. Nosotros somos eso para el poder central".

Dos décadas después, en un país otra vez al borde del abismo, la metáfora duele igual.