En un contexto de creciente conflictividad social en Argentina, marcado por protestas masivas de jubilados, trabajadores y estudiantes, el gobierno de Javier Milei afianza su alianza estratégica con Estados Unidos en materia de defensa y seguridad interior. Según informó el medio Info Defensa, efectivos argentinos participaron en junio de ejercicios conjuntos con la Guardia Nacional de Georgia en Fort Moore (ex Fort Benning), instalación históricamente ligada a la controversial Escuela de las Américas, donde décadas atrás se formaron militares latinoamericanos que luego integraron regímenes represivos.

El programa que puso en vigencia el gobierno de Mauricio Macri en 2016, promueve la "interoperabilidad" y el "entrenamiento mutuo" en tácticas de combate, ingeniería militar y respuesta a amenazas químicas o nucleares. Sin embargo, la elección del lugar no es trivial: Fort Benning albergó durante la Guerra Fría a la Escuela de las Américas, institución que capacitó a oficiales de las dictaduras del Cono Sur en doctrinas de "seguridad interna" y contrainsurgencia, bajo el paradigma estadounidense de combatir al "enemigo interno". Entre sus alumnos figuraron represores argentinos que luego aplicaron esos métodos en centros clandestinos durante el Proceso (1976-1983).

Coincidencia… o continuidad

La actual gestión insiste en identificar un "enemigo interno" en quienes protestan contra sus políticas. La ministra de Seguridad, Patricia Bullrich, viene impulsando protocolos que criminalizan la manifestación social, con un despliegue represivo que incluye gases lacrimógenos y detenciones arbitrarias, según denuncias de organismos como el CELS. Este enfoque, sumado a la retórica oficial que estigmatiza a opositores -desde sindicalistas hasta artistas, pasando por economistas y periodistas-, evoca el lenguaje previo a los años 70, cuando la Doctrina de Seguridad Nacional se usó para justificar la persecución, y en muchos casos la muerte, de disidentes.

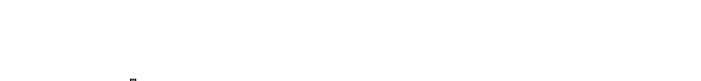

El Mayor General estadounidense Konata Crumbly y Brigadier argentino Gustavo Javier Valverde, luego de la firma que renueva el convenio que inauguró Mauricio Macri.

Aunque el gobierno argentino y sus socios estadounidenses enfatizan que la cooperación actual se limita a aspectos técnicos, expertos advierten sobre riesgos simbólicos y políticos. "El escenario es distinto: hoy hay democracia y marcos legales. Pero cuando un gobierno militariza la respuesta al conflicto social y retoma vínculos con centros asociados al pasado represivo, es inevitable preguntarse qué mensaje se envía a las Fuerzas Armadas", señala un informe del Centro de Militares para la Democracia (CeMiDa).

La memoria y el presente

Tras la restauración democrática en 1983, Argentina avanzó en la subordinación castrense al poder civil y en juicios por crímenes de lesa humanidad. No obstante, la reactivación de acuerdos en instalaciones como Fort Moore -ahora bajo otro nombre, pero con similar infraestructura- sin dudas reabre heridas. Para organizaciones de derechos humanos, la clave está en la transparencia: "Que no se repita la opacidad de los 70, cuando EE.UU. formó militares que luego usaron ese conocimiento para torturar", subraya el CELS.

El desafío, coinciden analistas, es garantizar que esta cooperación no legitime concepciones belicistas de la seguridad. Mientras el Ejército argentino insiste en su rol constitucional de defensa externa, las imágenes de gases lacrimógenos contra abuelos en Plaza de Mayo alimentan fantasmas que, para muchos, nunca se fueron del todo.